We’re still getting in a lot of data about COVID-19, but one thing is already clear: the disease has disproportionately affected people along racial, ethnic, and income lines. The phrase “social determinants of health” has been widely discussed in healthcare circles over the last year or so, and nowhere are the implications of where one lives and works on such stark display as when it comes to COVID-19 outcomes.

In this blog post, we’ll examine some of the racial, ethnic, and income data around COVID-19 outcomes and look at how the data can inform healthcare providers moving forward. Let’s take a look.

Minorities bear a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 deaths

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting black and Latinx people across the country. For example, among COVID-19 deaths in New York City in which race and ethnicity are known, death rates are:

- 3 deaths per 100,000 population for Black/African American persons

- 3 deaths per 100,000 for Hispanic/Latinx persons

- 2 deaths per 100,000 for White persons

- 5 deaths per 100,000 for Asian persons

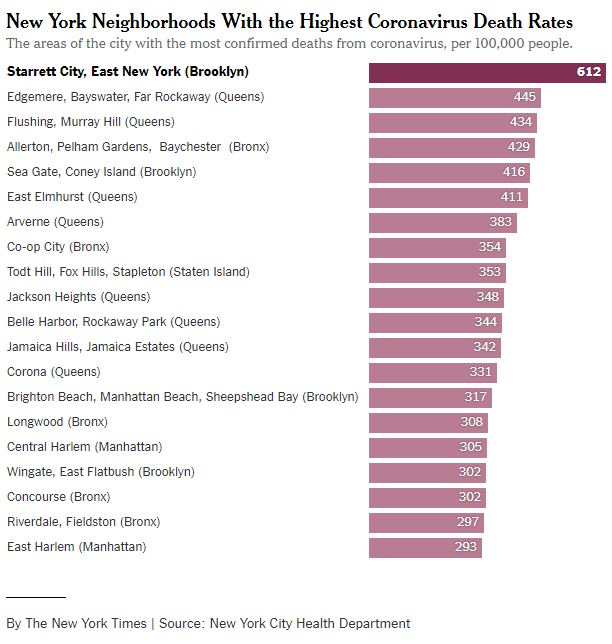

This data is eye-opening, showing that black New Yorkers are dying at a rate twice as high as white New Yorkers. We can look at the data in a more granular way as well and examine the death rates in certain neighborhoods to see which ZIP codes are most affected. Not surprisingly, those neighborhoods with high concentrations of black and Latinx people, as well as low-income residents, have the highest death rates, according to a recent data published in the New York Times.

Source: New York Times

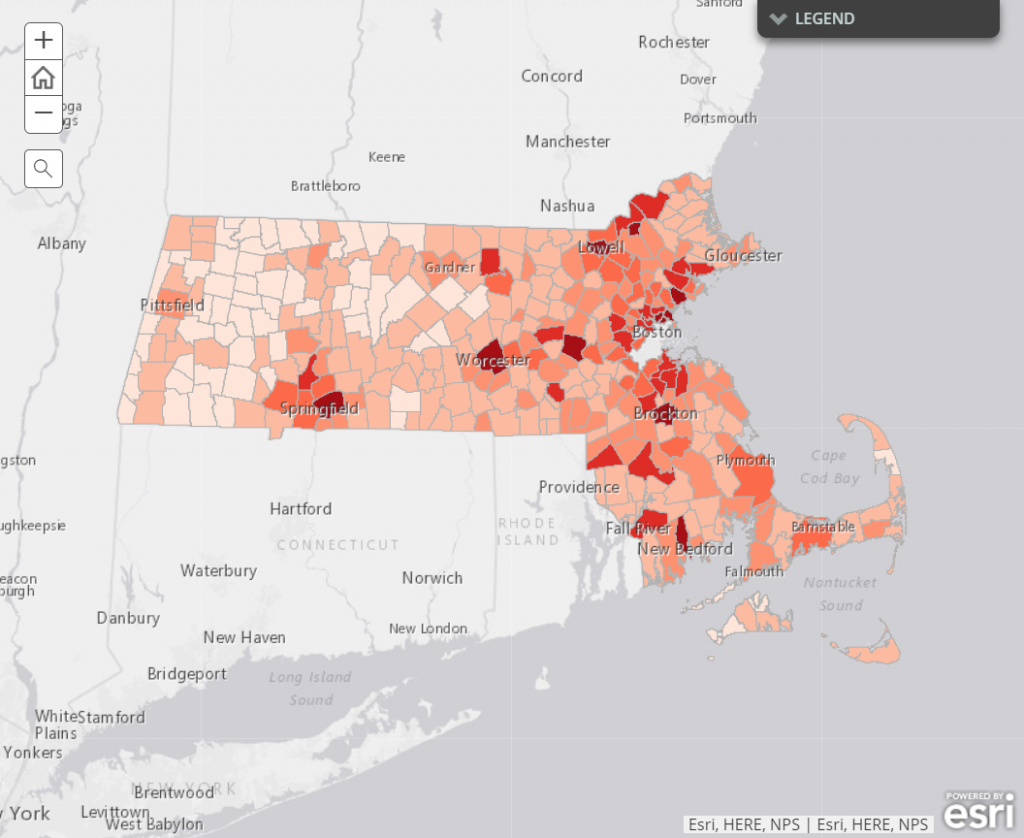

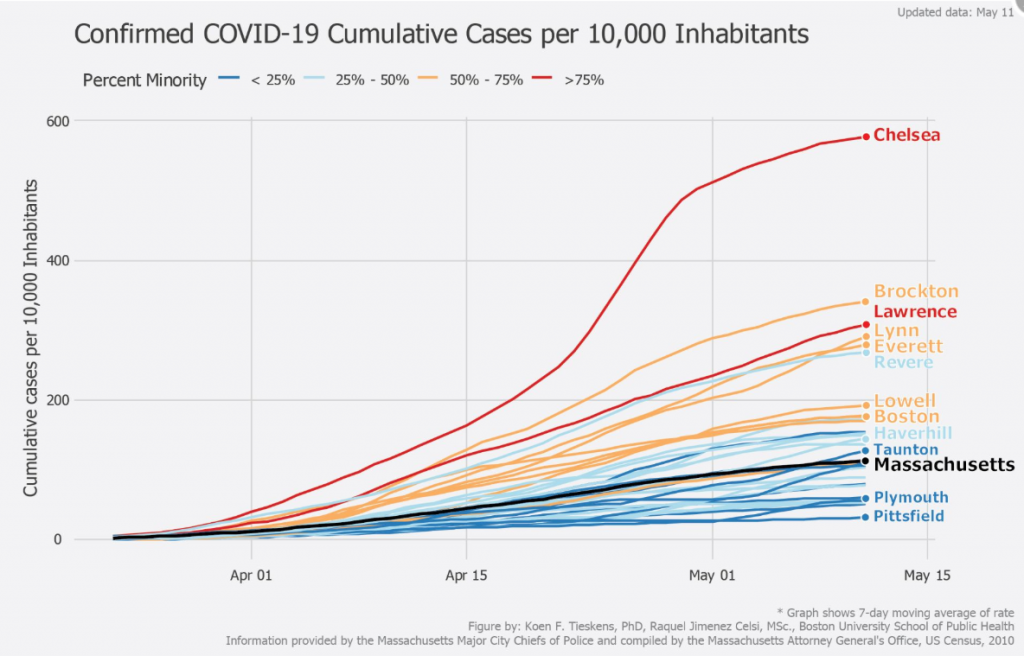

Data showing disparities across social determinant lines isn’t unique to the New York area. In Massachusetts, a group of students, teachers, and researchers at the Boston University School of Public Health created an interactive mapping tool that examines which cities and towns in Massachusetts are most feeling the effects of COVID-19.

In the map below, towns and cities that are a darker shade are more impacted by COVID-19. Not surprisingly, the impacted towns have higher percentages of minority populations, as shown by the graph below the map. In that graph, the red and yellow shaded communities have higher minority populations, while the blue shaded communities have lower minority populations. The difference in confirmed cases is stark.

Source: Boston University School of Public Health

Source: Boston University School of Public Health

How our environment impacts our health

To researchers who study social determinants of health, the data coming forth from COVID-19 underscores what they have already known for quite some time: the conditions in which we live and work have a profound impact on our health.

There are several reasons that minority populations are more impacted by COVID-19. Many of these are driven by economic factors in that minorities in the U.S. are more likely to live in lower-income communities. This affects factors such as:

- Housing: COVID-19 is more apt to spread in more dense housing environments, such as multi-family housing units. For example, the city in which I live is one of the dark red communities in the Massachusetts map above. As of May 16, our city had 1,418 confirmed COVID-19 cases. However, only 284 of those cases were among people who live in single-family houses. The rest live in multi-unit residences, long-term care facilities, and the state prison in the city. Because COVID-19 has such a comparatively high R-zero factor (the rate at which it spreads), those who live in closer quarters are more likely to get the virus from others in their community.

- Multi-generational households: In addition, many in lower income communities live in multi-generational households. This means it is harder to isolate the older household members who are more likely to suffer more the serious effects of COVID-19.

- Employment: While many transitioned to work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, this is less likely to be the case for those who live in lower-income communities. Lower-income workers are more likely to have jobs that require them to be outside the home, thereby increasing their risk of exposure.

- Co-morbidities: There is a wealth of research showing that those who live in lower-income settings are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, and obesity. These factors are also linked to greater complications when it comes to COVID-19. In addition, research has shown that the greater pollution one is exposed to, the higher the COVID-19 death rate since the disease impairs the lungs.

Using the data to improve decision-making

The data on social determinants of health and COVID-19 is certainly informative, but can the data also help us address the issues at hand? The optimist in me says yes, we can use this data to make better decisions. Here are some ideas.

- Point of care: The more physicians know about their patients, the better they are able to treat them. By integrating social determinants data into the EHR, physicians can better understand the areas in which their patients live and make more informed decisions based on that knowledge. In addition, flags and alerts can be set up so that hospitals and health systems have a better sense as to which patients in their ICUs or other units have co-morbidities, and can better tailor their treatments of those patients.

- Support for quarantined individuals: Not only can COVID-19 spread quickly among family members, but asymptomatic people can transmit the disease to others. That’s why it’s so important for family members of confirmed patients to be quarantined at home so they don’t unwittingly spread the disease. However, that’s a hard ask for those with lower incomes. These people are often on hourly salaries and live paycheck to paycheck. By better understanding the data about the community, local governments and support institutions can provide more tailored assistance to quarantined families, such as providing food and economic relief.

- Check your bias: Research studies have shown implicit bias from healthcare providers against minority populations. This systemic bias has resulted in worse care provided and lower health outcomes. While it’s certainly naïve to say that seeing social determinants data and noting the bias will erase that bias, it can be of use. Having an acute awareness of social disparities is an important first step that forces people to confront the issue. In turn, they may actively work to start to address it.

Conclusion

There’s obviously a lot of elements of the COVID-19 pandemic that are alarming, and the data surrounding social and racial disparities is one of them. The care provided to our neighbors and fellow citizens and the outcomes of that care need to be a top concern. The data on this issue can help shed a light on the problem, and hopefully, it can help us do some of the hard work needed to combat the disparities in our goal to provide high quality care to all.

- Navigating the Future: Trends in Wine Tasting Rooms - July 16, 2024

- Why You’ll Want to Attend DIUC24 - June 20, 2024

- The Role of Technology in Solving Nursing Challenges - May 6, 2024