We often talk about the effects that COVID-19 has on adults, since that is the age group that tends to be most affected by the virus. But has doing so created a blind spot in our precautions when it comes to infants and younger children? At the very beginning of the pandemic, little of our worry was focused on children — if any — because there were very few cases of babies and children contracting the virus. However, this may have led to the misconception that we can let our guard down when it comes to kids. Let’s examine.

A rise in cases

According to the CDC, during the period from February 12 to April 2, among 149,082 (99.6%) reported [COVID-19] cases for which age was known, only 2,572 (1.7%) were children under the age of 18. Fast forward just a couple of months and a study based on public data from The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association found that there were 74,160 new COVID-19 cases among children between August 6 and 21, 2020.

A few months ago, a well-known COVID-19 outbreak at a Georgia summer camp became a wake-up call for parents across the nation. “After a three-day orientation between trainees and staffers, 363 campers joined on June 21, but three days later, a teenage staffer fell ill and tested positive for COVID-19.” The campers were sent home, and of the 597 people at the camp, 344 were tested and 260 were COVID-19 positive. While the first person to contract the virus was a teenager, younger campers were among those who tested positive. The case seemed to foreshadow what was to come in the fall during the school year.

In fact, as of September 10, over 549,000 children have tested positive for COVID-19.

Risk

It’s clear that infants and children are not immune to this virus, but are the risks lower for them?

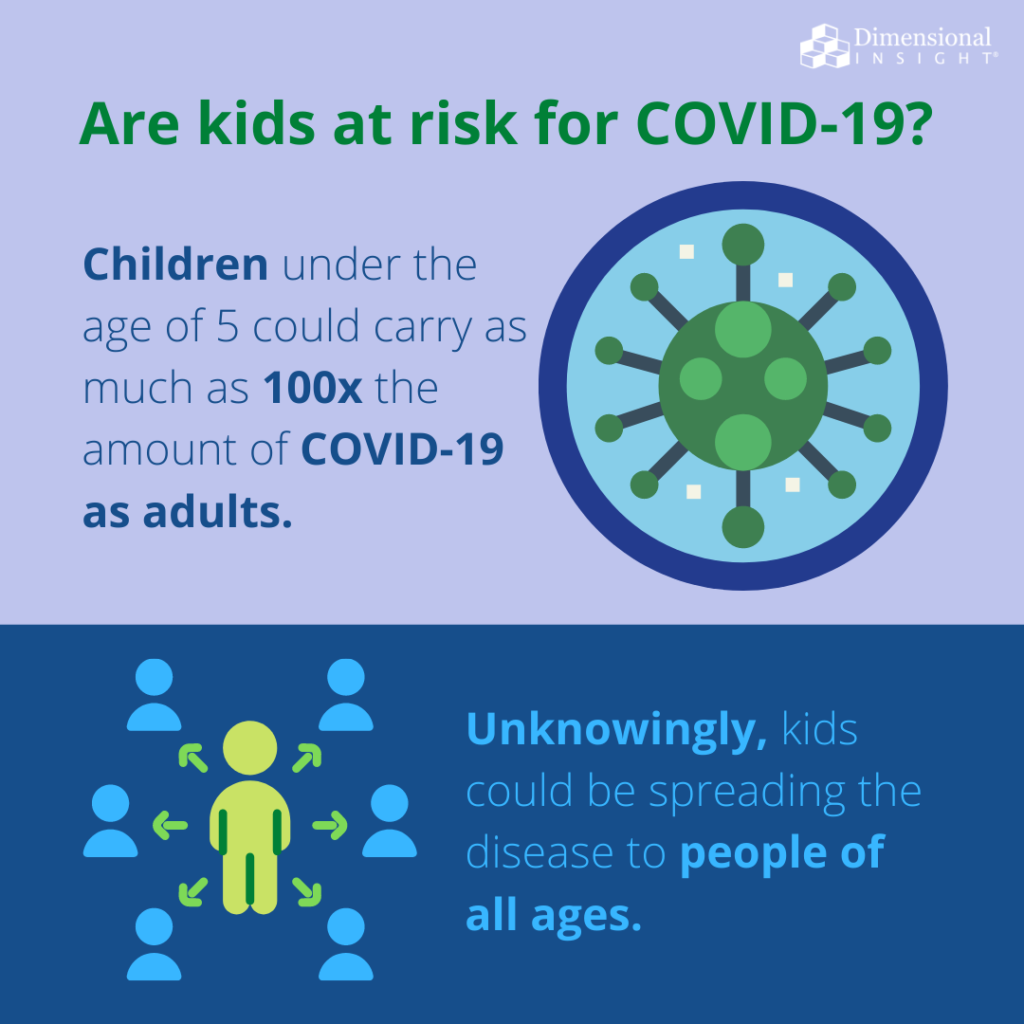

One study in JAMA Pediatrics found that children under the age of 5 could actually carry as much as 100 times the amount of COVID-19 as adults. While this doesn’t mean they’re more susceptible to the virus, it does mean they may spread the virus to people of all ages, even more so than adults — without showing any symptoms of having it. JAMA states that their “analyses suggest children younger than 5 years with mild to moderate COVID-19 have high amounts of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in their nasopharynx compared with older children and adults. Thus, younger children can potentially be important drivers of SARS-CoV-2 spread in the general population, as has been demonstrated with respiratory syncytial virus, where children with high viral loads are more likely to transmit.”

In a similar study, Massachusetts General Hospital and Mass General Hospital for Children found that while younger children are less likely to become infected or seriously ill from the virus, their viral load doesn’t decrease when they are infected with it, causing them to become more contagious to those around them.

“Their symptoms don’t correlate with exposure and infection,” said professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and study co-author, Alessio Fasano. “We have mainly screened symptomatic subjects, so we have reached the erroneous conclusion that the vast majority of people infected were adults. However, we should not discount children as potential spreaders for this virus. This should be taken into account in the planning stages for re-opening schools.”

Is my child too young to be tested for COVID-19?

It’s rare that testing sites allow young children to be tested. And as discussed above, many scientists and healthcare organizations were not focusing on the younger population since there were few hospital admissions in the age group. But as schools re-open, it’s important to allow tests on younger kids. States have different policies and many of them have minimum age limits to determine who is eligible for tests, but Sean O’Leary, a Colorado pediatrician who sits on the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on infection diseases emphasized that, “There is no good reason not to do it in kids. It’s a matter of people not being comfortable with doing it.”

In one case, Audrey Blute’s almost 2-year-old son, George, had a runny nose in July and for precautionary measures, Blute wanted to get him tested for COVID-19. However, due to the age restrictions, both the Washington, D.C. free testing site as well as her own pediatricians’ office denied her request to have George tested.

“We were told to assume that everyone in the household has it, which didn’t seem like the best information — we’re both big believers in contributing to the data pool and we think that’s really important,” says Blute.

As a result of being declined a test, Blute and her family isolated and worked from home. However, this is a privilege that not all families have. Some jobs are impossible to complete from home. If more children were able to get tested and be confirmed negative, such stress could be avoided.

Despite the additional squirminess and sensitivity younger children may have, the coronavirus test is administered the same exact way as it is to adults. But knowing that children and infants can carry and spread the virus easily, it’s even more urgent for healthcare organizations and testing sites to re-consider age limits.

Cold and flu vs. COVID-19

Cases of young children contracting the virus will only increase, and as the new school year begins it’s especially important to take the same precautions for your children as you do for yourself and older family members. Children who contract COVID-19 are more likely to require hospitalization if they’re under age two, Black and Latino, born prematurely, or are living with obesity or chronic lung disease, according to the CDC. Children’s COVID-19 symptoms are also often less severe than adult symptoms which makes it that much easier to brush off as a cold or the flu. Symptoms are generally similar among all age groups from babies to the elderly, but Johns Hopkins Medicine states that shortness of breath is more likely to be seen in adults. Additionally, children can have pneumonia with or without obvious symptoms, and experience sore throat, excessive fatigue, or diarrhea.

However, despite the rising cases, parents shouldn’t necessarily worry any more than they already are. Trusting their parental or guardian instincts if their child seems to be feeling sick, continuing to wear face masks, teaching proper hand-washing routines, and social distancing when possible are the best ways to keep the family and community safe.